After seven summers laboring on the farm, in 1885 the 18-year-old Wright gladly took a job with Allan D. Conover, an engineer and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was supervising the construction of the Science Hall on campus. Wright was tasked with designing steel clips to join the tower’s trusses but was met with frustrated craftsmen as the clips did not fit properly. Not bred as an armchair architect, and no matter the winter conditions or the tower’s height, Wright climbed up the steel beams to resolve his design and make sure they worked.

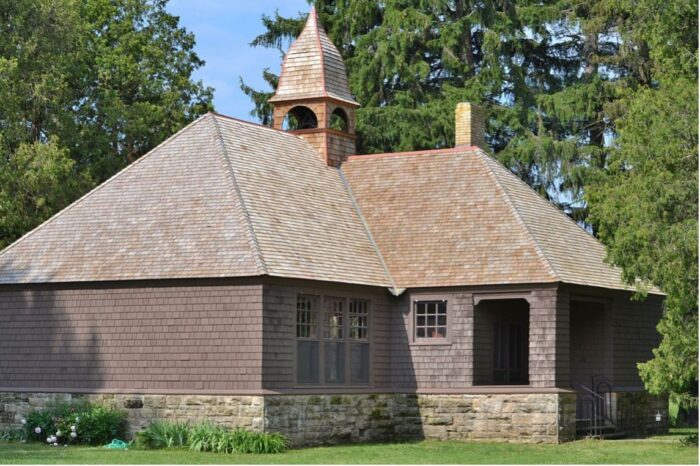

Photo by Nhi Tran

As a builder would, Wright scaled steel beams to the top of the Science Hall to fix his error.

This is the third post in a weekly series debunking the myth that Frank Lloyd Wright was only an architect. In fact, based on my research, he was first and foremost a builder. Here is a link to the first article in the series.

Wright took classes with Conover as a part-time student at the university, but realizing it was not the classroom but on jobsites and “..in that practice of his (Conover’s), that…[I] really learned most”, he moved on after two semesters.

Propelled by another of his mother’s brothers, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, a prominent minister, Wright was provided a platform to increase his construction experience. Wright helped build his uncle’s Unity Chapel, designed by respected architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee, in 1886. Wright then moved to Chicago and worked for a year under Silsbee before being hired at the office of Adler & Sullivan.

Photo by Stephen Matthew Milligan

Using carpentry skills acquired on one uncle’s farm, Wright helped another uncle construct Unity Chapel.

There he worked for Louis Sullivan, a pioneering innovator who termed the modernist guidepost “form follows function” and is known as the “father of skyscrapers”. Learning much as he served as chief draftsman and Sullivan’s literal right-hand man (his office positioned as such) Wright would later refer to Sullivan as his “Lieber Meister” (German for Beloved Master).

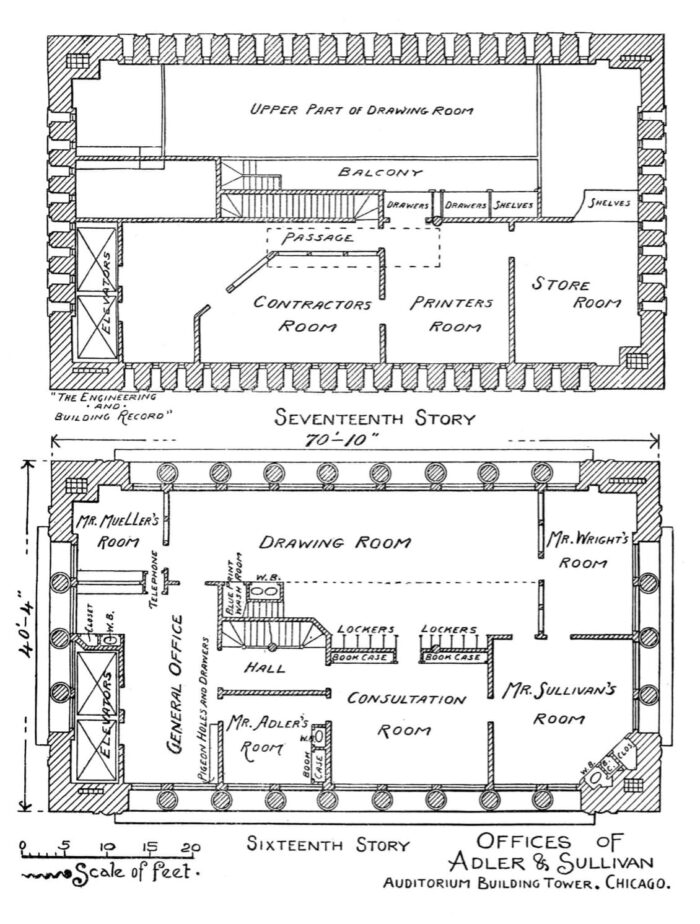

Surviving floor plans for Adler & Sullivan’s office hint to reinforcing Wright’s experience in the building trades and that the architect’s rightful place was to take full ownership for a project.

Engineering and Building Record, June 7, 1890, p. 5.

Note the top floor above Mr. Wright’s room (to the above right of Mr. Sullivan’s) housed a large “Contractors Room” – the firm oversaw the contractors and the building of their designs.

Unlike today where an architect (as merely a designer) is not responsible for the execution of a project, in Wright’s day the architect met with, selected and oversaw the construction of a project, often having one of their own employees acting as a superintendent on site. Here, the effectiveness of the architect being a single source of accountability for one’s clients, was reinforced with Wright.

Next week, I will share details on some of the buildings that Frank Lloyd Wright constructed.

Comments are closed here.